Ivermectin and Norovirus or Rotavirus

-

Ivermectin and Norovirus or Rotavirus

Over the past week my grandson, daughter, and now wife have all gotten sick with some form of stomach virus. 9 times out of 10 I am the one that gets sick, and my wife rarely ever. I haven’t gotten it (at least not yet).

I’m presently taking Ivermectin. I couldn’t help but wonder if this is what is protecting me.

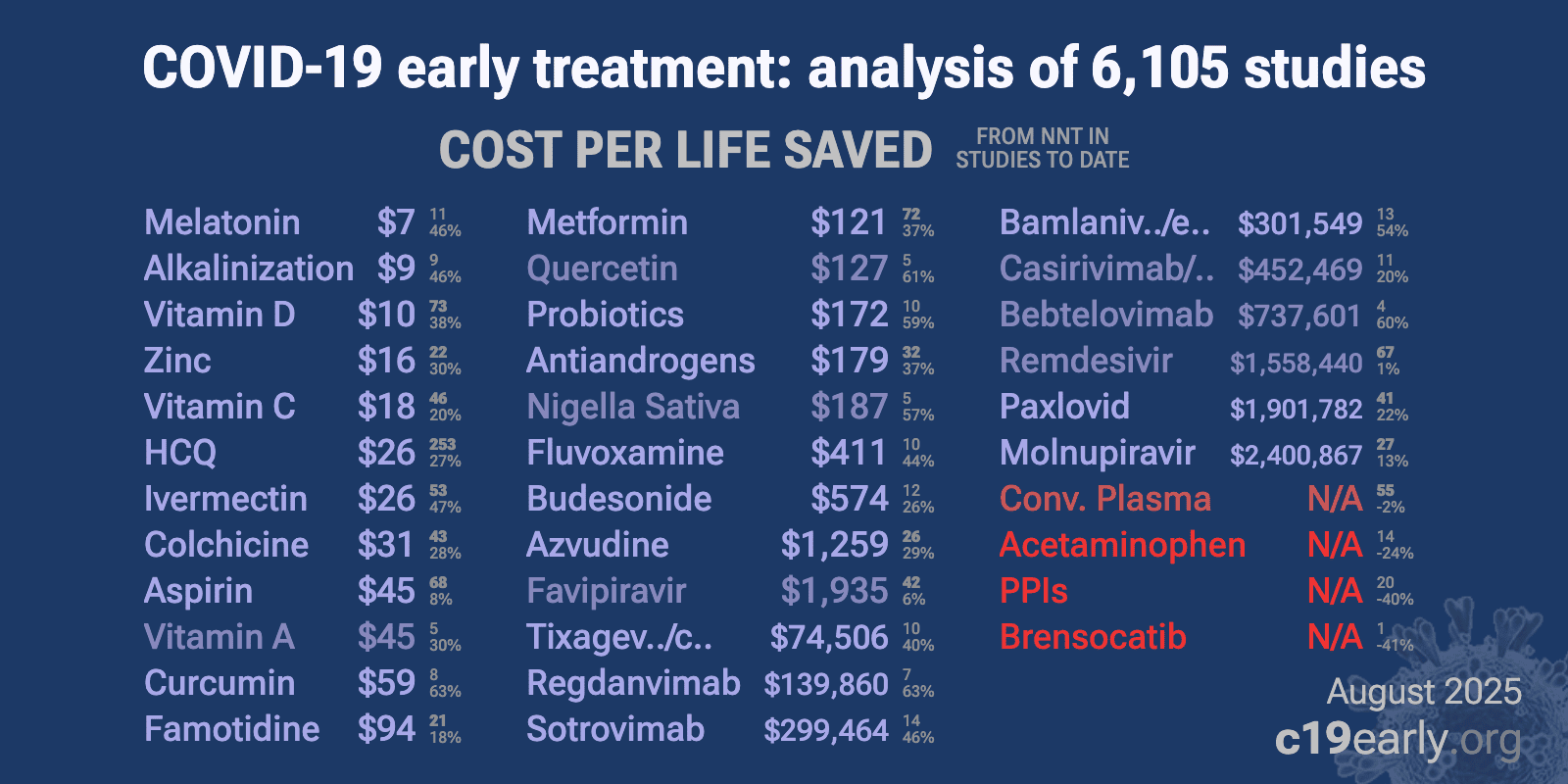

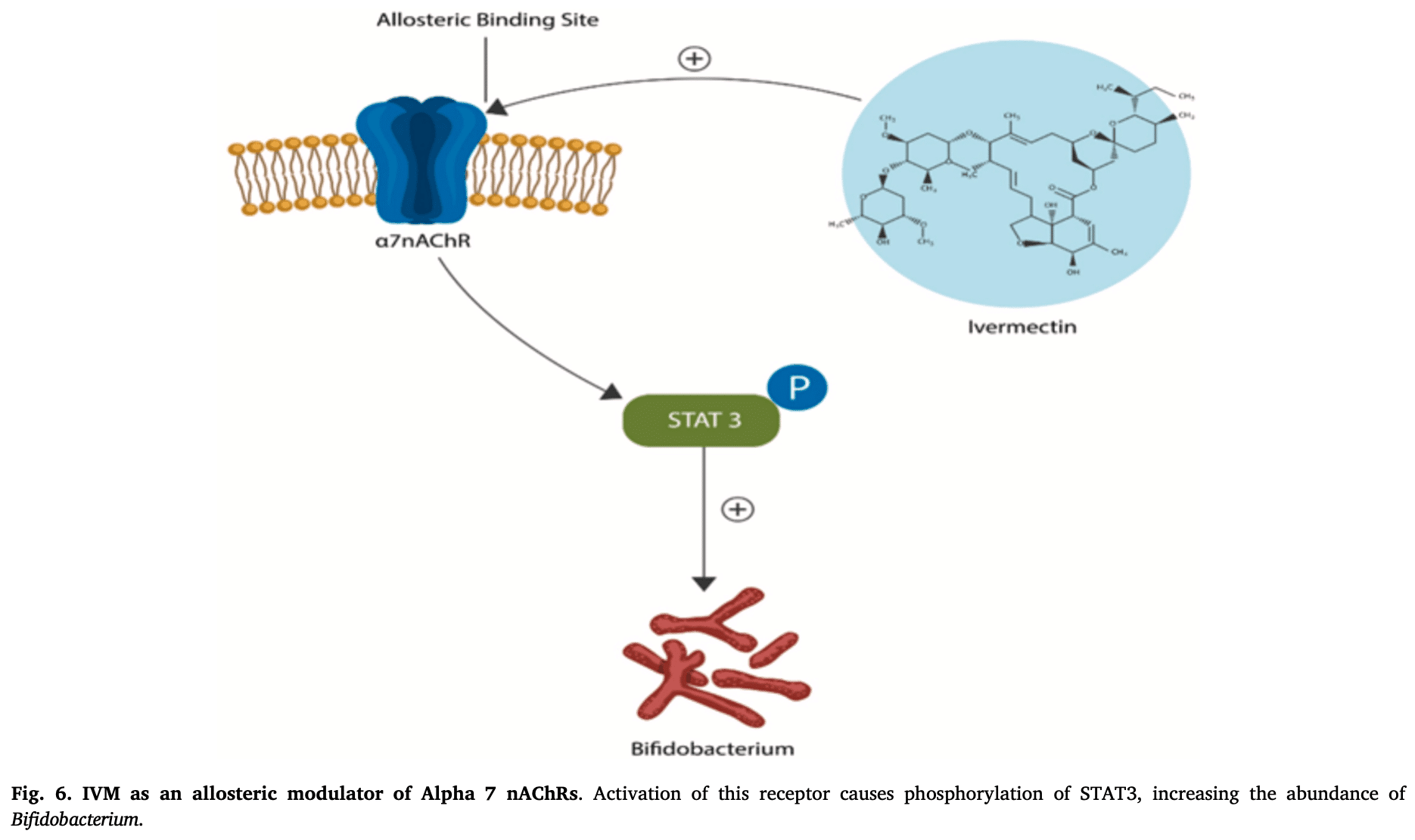

I know that COVID and spike protein deplete the body of Bifidobacterium and I know that Ivermectin increases Bifidobacterium (https://c19early.org/hazan8.html).

So, I was curious to ask Copilot what Bifidobacterium does functionally in the body and if it has any antiviral effects in the case of viral gastroenteritis. It appears my theory is correct. Taking Ivermectin causes an increase in Bifidobacterium and this in turn protects against viral gastroenteritis, along with other amazing effects.

Copilot:

Bifidobacterium appears to have several mechanisms that could help the body resist or recover from viral gastroenteritis—the kind of infection that causes vomiting and diarrhea from viruses like norovirus or rotavirus.

🛡 How Bifidobacterium May Protect Against Enteric Viruses

1. Strengthening the Gut Barrier

- Tight junction support – Certain Bifidobacterium strains increase the expression of proteins that seal the spaces between intestinal cells, making it harder for viruses to penetrate the gut lining.

- Mucus layer enhancement – They can stimulate mucus production, creating a physical barrier that traps viruses before they reach epithelial cells.

2. Direct Antiviral Effects

- Binding and blocking – Some strains can bind viral particles directly, preventing them from attaching to gut cells.

- Acidic environment – By producing acetate and other short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), they lower gut pH, which can reduce viral stability and infectivity.

3. Immune Modulation

- Innate immunity boost – Bifidobacterium can stimulate dendritic cells and macrophages to produce antiviral cytokines like interferon-α and interferon-β, which help limit viral replication.

- Adaptive immunity shaping – They promote IgA antibody production in the gut, which can neutralize viruses before they invade cells.

- Inflammation control – By balancing pro- and anti-inflammatory signals, they may reduce the tissue damage and fluid loss that worsen diarrhea.

4. Metabolite-Mediated Protection

- Acetate production – In mouse models, Bifidobacterium-produced acetate has been shown to protect against lethal enteric viral infection by enhancing epithelial cell antiviral defenses.

- Cross-talk with other microbes – They help maintain a balanced microbiota, which itself is part of the defense network against viral invasion.

📊 Evidence from Studies

- Rotavirus – Several clinical trials in infants have found that Bifidobacterium-containing probiotics can reduce the duration and severity of rotavirus diarrhea, likely through enhanced IgA responses and barrier protection.

- Norovirus – Human data are more limited, but in vitro and animal studies suggest certain strains can reduce viral binding and replication.

- General viral gastroenteritis – Reviews note that probiotics, including Bifidobacterium, can shorten illness duration and reduce stool frequency in acute infectious diarrhea, especially in children.

🔍 Key Takeaways

- Strain matters – Not all Bifidobacterium have the same antiviral effects; B. breve, B. longum, and B. lactis are among the most studied for enteric virus protection.

- Best results are preventive – Maintaining a healthy Bifidobacterium population through diet (prebiotics like inulin, resistant starch) or targeted probiotics may offer more protection than starting supplementation after infection begins.

- Immune and barrier effects work together – The antiviral benefit is not just about killing viruses, but about making the gut a less hospitable environment for them.

Log in to reply.